Sea Shanties ... Black Origins

A look into the origins of these wonderful songs is long overdue.

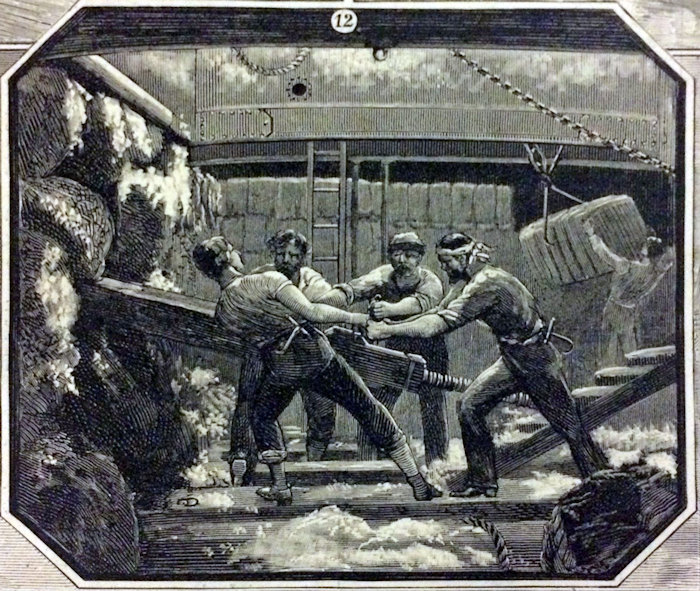

'Screwin' Cotton' by negroes loading on board ship Early Collectors The past year has seen a huge renewed interest in sea songs worldwide, largely due to a traditional New Zealand forebitter 'Soon may the Wellerman Come' becoming a number one chart success on both sides of the Atlantic. The year has also seen the publication of several new books on sea shanties. These include Gibb Schreffler's 'Boxing the Compass', Gerry Smyth's 'Sailor Song' not to mention my own trilogy 'Haul Away', 'Heave Away' and 'Sail Away'. I think a look into the origins of these wonderful songs is long overdue. Sea shanties, as we know them today, are very much a 19th Century phenomenon. They were sung by sailors aboard merchant vessels (not Navy ships where they were discouraged) and had their heyday from the 1830's to the 1880's' However they were still being collected from oral sources well into the 20th Century. They must have existed since ancient times and in fact are mentioned in print from ancient Greek manuscripts to texts from the 15th and 16th Century. There is little mention of them in the 17th Century and none at all in the 18th Century. The reason for this is almost certainly warfare. From 1700 to 1815 Britain was almost constantly at war and hence singing aboard ship would not be encouraged for fear of alerting any enemy ships. British merchant ships were also overmanned at this time for protection from piracy. During the same period, however, America was only at war for about 10 years (1775-1783 and 1812-1814) so shanties may have continued to develop on that side of the Atlantic. What we know about shanties we have learned from written sources giving 'ear-witness' accounts of their being sung at sea. These were published in books or magazine articles in the UK and USA. Apart from the ancient texts mentioned above the earliest reference to shanty singing is in 1811 in Robert Hay's memoirs 'Landsman Hay'. On a voyage to Jamaica in the merchant vessel 'Edward' he heard negroes singing the shanties 'OH, HURO, ME BOYS' and 'GROG TIME OF DAY' (both now sadly lost). In 'Two Years Before the Mast' Richard Dana heard shanties sung aboard the American ships 'Pilgrim' and 'Alert' between 1834 and 1836 where he says the crew was a mixture of 'English, Scotch, German, French, African, South Sea Islands plus a few Boston and Cape Cod boys' (a very multi-ethnic crew!). He mentions the singing of 10 shanties, all now seemingly lost apart from 'CHEERILY MEN', 'ROLL THE OLD CHARIOT' and 'ROUND THE CORNER (SALLY?)' Captain Frederick Marryat, author of the semi-autobiographical novel 'Mr. Midshipman Easy' (1836) heard black crew members singing shanties aboard a 'packet' he sailed in from England to America including 'SALLY BROWN'. Also, the naval historian Leonard G. Carr Laughton in 'Shantying and Shanties' wrote: 'In the 1830's loading of cotton on to ships gave seamen the opportunity to listen to slave songs and take them to sea as shanties. He cites 'WESTERN OCEAN' (LEAVE HER, JOHNNY?) and 'KNOCK A MAN DOWN' (BLOW THE MAN DOWN?)'' as examples. In 1886 James Taft Hatfield was a passenger on the three-masted barque 'Ahkera' from Pensacola, Florida to Nice, France. He recounted that the crew consisted entirely of 'Black men from Jamaica' among which several acted as shantyman. He requested the shanty-singers to begin the songs again and again until he could note the exact timing and melody. From them he obtained 'RIO GRANDE', 'BLOW THE MAN DOWN', 'RANZO', 'WHISKEY JOHNNY', 'SHAKE HER UP' and 'WE'RE ALL BOUND TO GO' as well as three previously unknown shanties 'SHINY-O', 'NANCY RHEE' and 'WAY DOWN LOW'. These were given to the 'Journal of American Folklore' by his daughter in 1946 Captain Frank Shaw in 'The Splendour of the Seas' says 'Many songs are undoubtedly of American origin and some of plantation origin, down to a fine point' giving as an example 'ROLL THE COTTON DOWN'. He continues 'After harvest … slaves were most costly to support in the winter months. The owners found a solution to this recurring problem. They hired them out as crews for America's growing mercantile marine'. William L. Alden in 'Sailors'Songs' also concluded that 'many chanties had their origins in black music'. Of course, many of our shanties are European in origin particularly from the British Isles. However, it must be acknowledged that a very large portion, possibly the majority, hail from black African-American and West Indian sources. These were predominantly slave songs, plantation songs and songs of black stevedores and hoosiers loading ships manned by white sailors who copied and developed them: 'Since the blacks used their own jabber … the borrowers fitted their own words to the catchy tunes … often ribald and obscene' (Frank Shaw). It seems increasingly obvious that shanties have arisen from and devolved from black work songs. Indeed, the American folklorist Stuart Frank remarked that 'The practice of shantying on shipboard is descended from West African work songs'. Twentieth Century Collectors Many 20th Century collectors including the folklorist Alan Lomax have 'discovered' pulling shanties from black sources in Florida, Georgia Sea Islands and the Bahamas including such favourites as 'SAILBOAT MALARKEY' and 'LONG SUMMERS DAY' and the shanties of the black menhaden fishermen from the USA's East Coast (mainly Virginia and North Carolina) have yielded such gems as 'JOHNSON GIRLS', DRINKING THAT WINE' and 'WON'T YOU HELP ME TO RAISE 'EM'. There have also been several studies of 'Caribbean' shanties, the best known being the collection of essays 'Deep the Water, Shallow the Shore' by Roger D. Abrahams in the early 1960's. He noted that the use of shanties was 'everywhere' in the Caribbean and not just limited to ship-board work. Such shanties as 'JOHN DEAD' and 'BLACKBIRD GET UP' have become very popular with modern shanty singers from this collection. Our greatest shanty collector Stan Hugill ascribed about 120 of the shanties from his 'bible' 'Shanties from the Seven Seas' (1961) to Black American and Caribbean origins. These were mostly collected from his West Indian informants Harding the Barbadian, Tobago Smith and 'Harry Lauder' from the Island of St. Lucia. He even tried to imitate the yelps and 'hitches' these black shantymen put into their singing of the shanties. Many of these had never appeared in a shanty collection before including 'ESSEQUIBO RIVER', ROLL,BOYS.ROLL' and 'WHERE AM I TO GO'. He also collected the great favourite South Sea Island shanty 'JOHN KANAKA' which he claimed was 'one of a body of Poynesian shanties'. Stan also made frequent reference to his experience of 'checkerboard crews' (one watch black and one watch white) where shanty-swapping must have occurred. Many of Stan's shanties had previously been put in print by British collectors without any mention of their negro origin. These include 'BULLY IN THE ALLEY' (Cecil Sharp), 'COME ROLL ME OVER' (John Masefield), 'HILO, BOYS, HILO' (Richard Runciman Terry) and 'PAY ME THE MONEY DOWN' (Laura Alexandrine Smith). Of course, Hugill was a shantyman himself and shipped as a common sailor in the fo'c'sle. Most of the other collectors did not have this experience. The only other major British collector who worked as a common seaman and shantyman was the author Frank Thomas Bullen who along with his friend W.F.Arnold wrote 'Songs of Sea Labour' in 1914 just six months before his death. He writes of his first sea voyage in 1869 at the age of 11 and hearing his first shanty 'MUDDER DINAH' when discharging cargo in the Demerara River, Georgetown (Guyana). I concentrated my attention upon learning the songs I heard (every day for about a month). Bullen places 'MUDDER DINAH' as number one in his collection followed by other negro shanties he learnt: 'SISTER SEUSAN', 'TEN STONE', 'SHENANDOAH', 'SALLY BROWN', 'WALK ALONG ROSEY', 'LIZA LEE', 'LOWLANDS AWAY' and 'POOR LUCY ANNA' As for the rest of the 40 shanties in his collection Bullen states 'the great majority of these tunes undoubtedly emanated from the negroes of the Antilles (West Indies) and the Southern states, a most tuneful race if ever there was one, men moreover who seemed unable to pick up a ropeyarn without a song'. Unfortunately, the well respected poet and shanty collector Cicely Fox Smith dismissed Bullen saying he 'had n****r on the brain'. Her American contemporary Joanna Colcord (both were born in 1882) had a different opinion commenting in 'Roll and Go' (1924) that 'the American Negroes were the best singers that ever lifted a shanty aboard ship'. The only other major American collector to credit African-American work-songs as a major contributor to shanties was James Madison Carpenter who did most of his collecting in the British Isles in 1928 and 1929 using a wax cylinder recording machine. He wrote in The New York Times Carpenter's huge collection of 98 different shanties from nearly 400 recordings gave us black shanties such as 'DOWN TRINIDAD', 'LONDON JULIE', 'PULL DOWN BELOW' and 'NOTHIN' BUT A HUMBUG'. The first of these was collected from Richard Warner in Cardiff in 1928. Warner had first shipped in 1877 and learned this song on S.S.Bananzo in a sugarlog station in Barbados.The last two were among fifteen collected in 1928 in South Wales from Rees Baldwin who told Carpenter he had learned shanties from 'Negro singers in Savannah and New Orleans'. Carpenter describes many of the shanties he collected as 'of negro origin'. Sadly, apart from Hugill and Bullen, no other major British collector seems to acknowledge the black origins of some of the shanties they collected. Most seemed keen to promote them as part of an English folklore heritage. Consequently the revivals in shanty singing and folk singing that occurred in the 1920's and 1960's assumed this to be the case. With the new worldwide revival in interest in shanties that has begun it is important that we portray them as 'world music' with a multi-ethnic background with particular emphasis on the black origins of many of them.

'All the wonder I could spare was given to the amazing negroes who, not content with flinging their bodies about as they hove at the winch, sang as if their lives depended upon maintaining the volume of sound at the same time … I have never seen any men working harder or more gaily than negroes when they were allowed to sing'.

'Being extremely fond of singing I became most anxious to learn it, so I asked one of our two boat-boys to teach me. Had I offered him a sovereign he could not have been more delighted. He set about his pleasant task at once but was very soon pulled up by his mate who demanded in indignant tones what he meant by teaching 'dat buckra chile (white boy) dem rude words'.

'These working choruses, frequently taken from the Negro labourers of different countries, especially the Southern States, existed in large numbers, for the Negro required a song to lighten his work'

'Indeed, it is not surprising to find a fairly large proportion of the chanteys coming from the American South. Chanteymen were naturally quick to press into service aboard ship the Negro gang-work songs- with their droll fun, languorous cadences, and well-worn rhythm'.